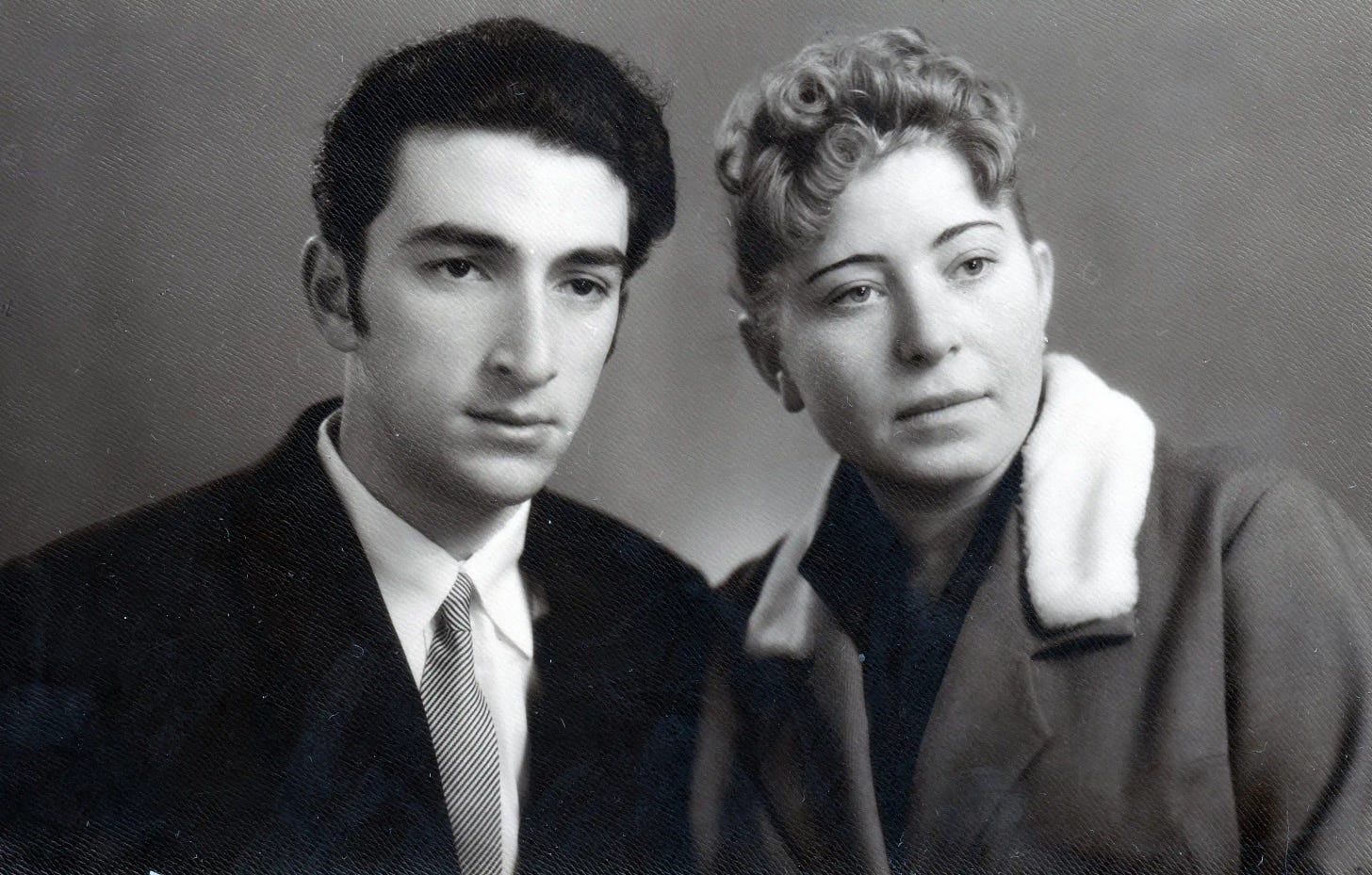

My grandpa Alik and my grandma Emma, soviet Russia, Lenin behind them. My dad sent me this photo recently and said "“Look at how Alik looks at Emma. They both looked like they had accomplished so so much. They had a CAR. And each other. They MADE it.”

It is the 10th of February at 2:30pm, and something is wrong.

I’m driving home on the phone with my dad who is not so subtly suggesting that I need to call my grandpa Alik: Alik is lonely in Milwaukee, why not just give him a call, it will take two minutes, what, you don’t have two minutes?

I want to explain that of course I have two minutes and I DO try to call, but often it feels like there’s nothing to talk about. Even if by some Soviet chudo (russian for miracle), my Russian speaking skills magically evolved from that of a first grader who hates school into a top Russian scholar, even then I would never be able to really explain how I’m doing.

There’s simply no way to explain “Hi just launched paid subscriptions on my substack so people can pay if they want to but they don't have to all the content I put out is still free and its going really well but I actually don't look at the numbers anymore because I was looking at them too much and it was making me depressed which, combined with my ocd and adhd, is a real dumper of a mental health trio."

Also, why can’t he call me!? I’m busy with shit and he’s…we’ll, he’s not doing a lot so…?

I can’t explain this all to my dad - he, along with Alik and the rest of my fam, live on one side of an invisible Berlin Wall that separates me, the English speaking American boy bred amidst democracy from them, the Russian speaking, Soviet family raised inside a failed Communist / Socialist regime.

As I’ve written about several times now, the gift my parents gave me by moving to America when I was seven was the inability to understand them.

So instead of arguing I just say, aspiring, “okay yea I’ll call him,” hang up, and drive on, wondering what rifts will soon exist between me and my ten month old baby son Wilder who, at this moment sits in the backseat, yawning dramatically, like jeez dude we get it, so I turn up the 88.5 K-Jazz to keep him awake before his afternoon nap.

But something is wrong. We are 0.2 miles from home when my 2009 Prius - color Onyx, name also Onyx - begins to sputter, then stutter, and finally putter, inching forward on fumes and fumes alone.

I push the gas, but nothing happens - Onyx does not go, so I scream “don’t you die on me you son of a bitch” (onlookers dispute this), and push the gas again, but still, nothing. We’ve got a little forward momentum drifting us forward, but will it be enough to get us home? I do not know. Slowly we make it to the right turn onto my street, going further still and, in a miracle the likes of which this world has not seen since the Chanukah oil lasting eight full days - Onyx makes it all the way up to the tip of my driveway and then, finally, he dies. Close, but there is no cigar.

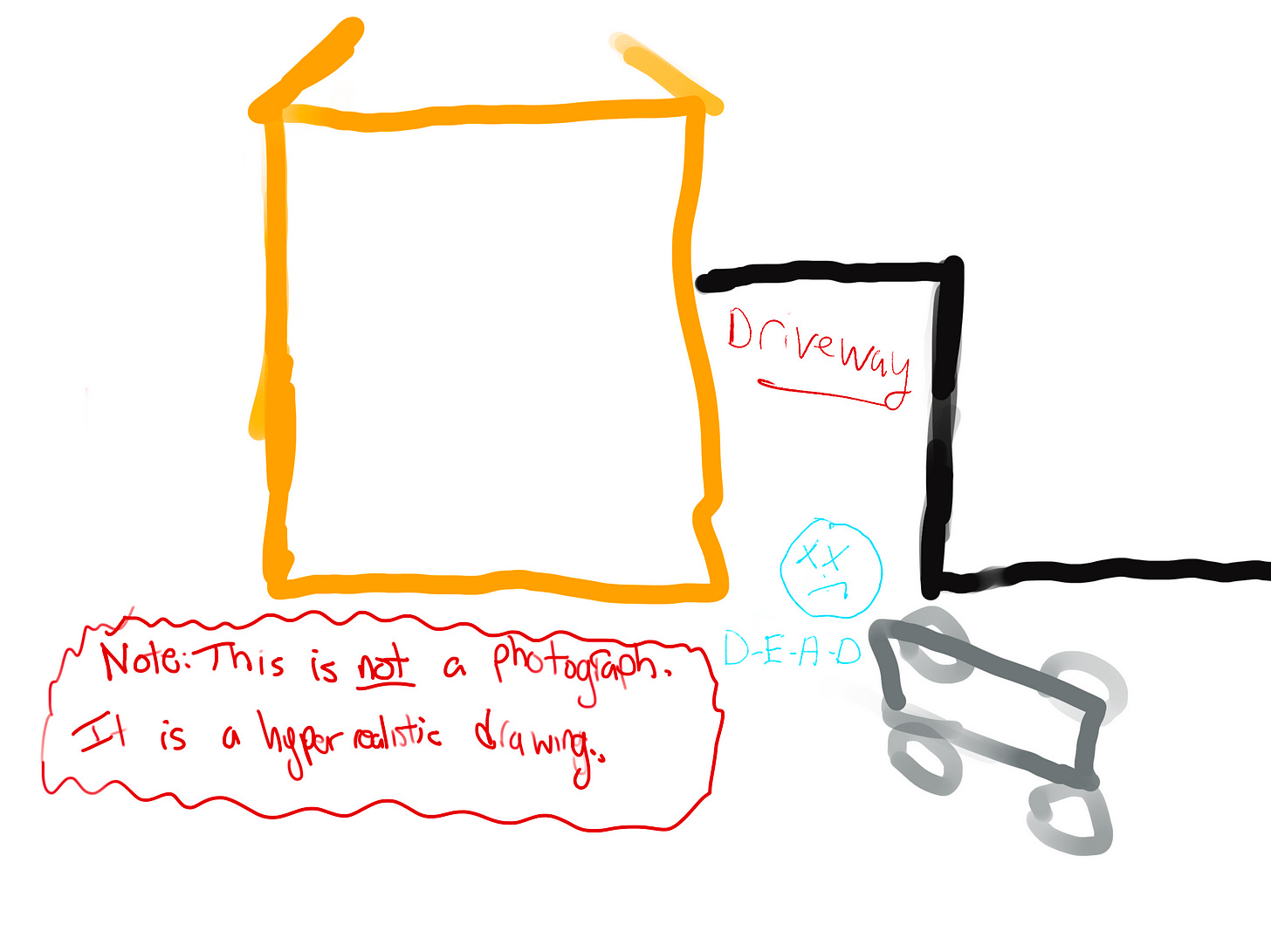

I’m a visual person, so here’s a hyper realistic drawing of the scene. Do not be fooled, this is NOT a photograph.

After handing the blissfully unawares baby, still babbling to himself as if life is one giant jar of marmalade, to our babysitter, I approach Onyx, his ass out for the whole neighborhood to see1.

Then I try to give Onyx car CPR aka CCPR: ignite, damn it! Nothing.

He is no longer pro or against, he is N for neutral, which is also the only gear he’ll go into.

Luckily for us, my attitude is staying P for Positive because I know exactly what to do. Having been raised on a healthy diet of 90s sitcoms + rom-coms from the early aughts, I am of the firm belief that it’s super easy to push a real life car made of real life metal with my tiny little 155 pound human body! Sure there’s grunting and an absolutely classic 1,2,3, PUSH countdown, but the hero always gets it done, right?

NO not fucking right, very wrong actually. Believe it or not, pushing a car is HARD. Cars are HEAVY.

Within minutes, I’m drenched in sweat, pushing and heaving and grunting, all to no avail. I consider giving up, letting Onyx trample me and ending this charade as my son watches on, through the front window, uttering his first words “dang, dad really sucks.” But then I hear a voice.

“Hey man, you need help?”

Squinting through salty beads of sweat, I see a blob. Backlit by the sun, the blob approaches and morphs into a man - mid twenties with jet black hair, he says his name is Mosh, though to me, he is Jesus.

Jesus, ladies and gentlemen, has finally taken the wheel.

Well, sort of. MoshJesus (MJ) looks down at his sandal clad feet and goes “ah man I need shoes.”

I try to tell him that actually I’m pretty sure sandals are actually a big part of the OG JC’s brand, but I’m Jewish and he, well he’s MJC, so I say nothing and watch him go.

I wish I could say that right there, red pilled on the fragility of life, staring down the death of my car and best friend Onyx, I pick up the phone, tears and alsos sweat streaming down my face, and call Alik. I’d say everything I’ve ever wanted to say but couldn’t before, and so would he - we’d finally connect.

But much like the film Cars, that is an animated fantasy. And this? This is life, so I just sort of stand there, sweating and praying and crying (my big 3!) until MJC returns with some dope, very on-brand all white Nike’s.

I look to MJC and say (with my eyes): “hey remember the whole one-set-of-footprints-in-the-sand thing, when your dad (God) carried whoever wrote the ? this is that moment. Carry me.”

And he looks back and says “ready?” because I’ve said nothing and he cannot speak ‘eye,’ so I say “let’s do it “ and without even a 3,2,1 countdown (!), we push and push and push and I think, “man, I finally understand the pain of childbirth and feel as though I have gone through it myself, a fact that I am excited to soon share with the mother of my child!” Then I black out.

I come to a few seconds later to find that, praise MJC, we did it: Onyx is in the driveway. MoshJesus walks on, ready to save the next soul, as I stand there, sweaty and near death myself, glad that at least Onyx died peacefully, in his own home.

The next morning I call my far away parents in a far away land (Rhode Island) and tell them what happened. They respond, calm as two cucumbers, “you have a cousin in LA named Lenia who runs a car repair shop called Citizen Collision that just so happens to specialize in priuses.”

I have lived in LA for 10 years. this is the first time I’ve heard about Len and his shop. The lord, father of MoshJesus, works in mysterious ways.

I get my ‘friends’ at triple A (AAA) to tow Onyx to my ‘family’ at Citizen Collision (CC). Then I pray.

Who is Alik really?

Never has the death of a car been more eloquently described than by Nux, the philosopher with a butthole mouth in Mad Max: Fury Road:

“I live, I die, I live again!”

Much like cats, cars have many lives. People, not so much. People live, they die, they...well, they stay dead.

I know Alik won’t be around forever. But still I struggle to take the few minutes it’d take to call him. And I feel guilty—a present day regret for a future that hasn’t yet arrived, like I wish I had called him more when he was alive, but he is still alive, and I could still call, like right now, but....I don’t.

Why the fuck not?

Grandparents are a fascinating contradiction - they are some of the closest family you have and yet your lives could not be more different. I understand the truth of Alik’s life less than I understand about the dude who works at Ralphs and told me, in great detail, about the Rammstein concert he attended last night2.

The folklore of family

What I do know of Alik feels like legend - he is a mythical being, a god in the pantheon of Dobrenko lore.

Alik didn’t have a childhood, the stories go. His father and two older brothers went to fight in WWII leaving him, his sister, and his mother, who had recently broken several bones falling out of a second story window, to flee their home for the hills of Uzbekistan. They’d spend the next four years there, 1941 - 1945, a broken family whose matriarch was herself broken. From age two, Alik grew up in a world where there was no time for play, no time to be a child. When the war ended, they returned home to learn that Alik’s father, wounded in the war, had died on his return trip home. He was six years old, without a father, knowing only the misery and displacement of war.

At age fourteen, he went to work. His first job was doing manual labor at a fabric factory, a job he would do for the next forty years. It would have been longer, too, but the Dobrenkos made a move to the land of almond milk and raw honey: America.

When I think about Alik, the first thing that comes to mind is how, whenever I visit him in Milwaukee, he will greet me at the airport, the same giant puffy black coat on regardless of the weather, and take my face into his gigantic calloused, meaty paw of a hand, and says “Dobrenka”, like I am one of the Dobrenko clan.

Then he’ll grab me into a bear hug -- close but not too tight, like a mafia don (Donbrenko), and top it off with some dumb, sarcastic joke into my ear. People can’t ever tell when he’s kidding and when he’s serious, like he exists in that liminal space, that hazy intersection between joke and truth where there is no longer a difference between the two. It is poetic, profound, and definitely a huge influence in my comedy, my outlook, my life. He would never describe it this way though. “What are you talking about,” he’d say, but with a lot more swear words. He makes swearing in Russian look cool, too. He is cool, period. I mean, look at this:

Alik loves cars. Like my dad, he always asks me about my car when we’re on the phone. First they ask about the weather, then how I’m feeling and work and family, and finally, always, “how’s your car?”

In Russia, my dad explained, the health of your car was not something you could ever take for granted - cars broke down all the time and if yours did, you were screwed, thus elevating the question of ‘how’s your car doing’ to the list of things to always check in about with your loved ones - essential, existential, core.

This, I realized, was my way in. I’d call Alik and tell him about Onyx and our recent misadventures and we’d finally connect!

A New Hope

Back to Onyx. A few days later my phone buzzes with a text from my dad’s cousin brother Lenia- “Car is ready.”

In the Uber on the way to Lenia’s shop, the land of citizens who have been in collisions, I realize that I have no idea what my dad’s ‘cousin’ looks like3. I assume he’ll just look like my grandpa Alik. Maybe Alik will even walk out and say hi and we’ll laugh and talk and - no, that’s not Alik. That’s a short man with a short white haircut, glasses, and a big ol white mustache. That is Len.

Len takes me outside, and right away I see my car. My Onyx.

I approach it, teary eyed and ready for an emotional reunion when he says “that’s not your car. That’s my car. Yours is over there.”

Turns out I don’t know what my own car looks like. And me and Len have the same car. A sign? They are everywhere. All you gotta do is look.

Hey siri, call Alik

I call Alik on the drive home, excited to share the news of Onyx’s near death experience as an absolute banger of an answer to the ‘how’s your car’ question. Hope abounds!

Alik picks up the phone and...he sounds tired. Sad maybe. Maybe he woke up from a nap or maybe he's deep in the depression he's been in since my grandma died four years ago. He visits her tombstone every Sunday, spending hours there, cleaning it, talking to her. She was his life and she is gone.

Our convo follows the usual script:

How’s Wilder?

Good, he’s walking. How are you?

Good good. How’s Lauren?

Good….

How’s work?

Good, I’m writing yea work is great.

(Again, I refrain from the details: “work is great I’m working on a pilot that’s being funded by a company in the medical space that wants to get into content - who doesn’t these days - but I think they’re actually gonna shoot it as a pilot and then try to sell it to a streamer, maybe Apple, who knows. Regardless we can release the pilot as mini digital episodes, which is cool.”)

Then the much anticipated question: How’s your car?

I try to explain the story of Onyx, MoshJesus, and all the rest but when translated into my shit Russian it shrinks into “My car died and I took it to Lenia’s shop. Do you know Lenia?”

He does.

Another causality of our move to America. Bridging the gap between two generations is hard enough without the oceans of difference in politics, customs, and culture. Oh and let’s not forget - we don’t speak the same language! Not really. I speak Russian like an anxious six year old with big adult ideas in his mind that he just can’t figure out how to put into words. Alik speaks English the same, except with the anger of having to use a language that he learned when he was in his fifties. Was coming here worth all this? I have no idea.

When we came to America, I was six years old and I had one mission: fit in with all these abercrombie and fitch americans. I stopped speaking Russian at home, watched as much Saved By The Bell as possible, became obsessed with basketball and pro wrestling, and successfully and in pretty short order became someone who resembled an American. Close, but no cigar. I was stuck between worlds - no longer Russian and definitely not really an American. In limbo, then and now. Except now I crave to connect with my past, my culture and family, but I can’t.

A silence in our convo that feels as long as the last two paragraphs is finally broken when Alik speaks again:

How far is the auto shop from your place? !! Progress!

I tell him "not far, about 15 minutes."

That’s good.

And then, much like Onyx, the convo dies.

When in doubt, write it out

I spend the next few weeks obsessing over how to end this cold war. Frustrated, I try writing out a text message to send to him, being super honest about how I feel:

dad keeps telling me to call you. I want to call you but I don't know what to talk about. Me and you both hate small talk, so what should we talk about? I sometimes feel like you don't want to talk. So I feel like a failure when I call.

I run it through Google Translate and read it back, but it sounds wrong, robotic, and, most of all, angry. The tone is off, pissy and self righteous. The man has been through so much and I’m gonna hit him with some angsty bullshit? No.

Defeated, I get home and allow the jumbled mess of baby, marriage, job, god and country to swallow me whole. Days become weeks which, spoiler alert, become months. Seven months to be exact, during which Alik and I never connected, not really, not like I wanted. Not for real.

The story was over. Or so I thought until, much like the USA beating Russia that one time in the Olympics, another miracle happened: Onyx died again.

Seven Months Later

Onyx was hyperventilating, wheezing metallic when I pulled onto the side of the road to see what was happening. I get out of the car and pull out my phone to take a video for Lenia when, and this is no joke, my phone is calling my grandpa.

I will repeat: my phone butt dialed my grandpa.

It could only be MoshJesus, the son of the lord, partnering with Onyx (MJ x Onyx) for the collab of the century. I’m starting to think maybe I’m a miracle magnet or something when I remember how much I’ve been wanting to connect with Alik.

Lenia says to bring Onyx into the shop - he will take a look, so we drive home, Onyx wheezing and me obsessing once again over how to change the dynamic between Alik and I - to give it a spark of something new, to wake us both up and actually talk. But I have no good ideas and get mad again, thinking about why he won’t just call me when I realize - I can’t control what he does. I can control what I do.

I get home - Onyx is totally fine by the way - classic false alarm to make your bff / owner realize that he has unfinished business with his gramps - and I write a list of questions I want to ask Alik. Things I’m genuinely curious about. My dad translates the list and I send it off4. Then I wait and again I pray by which I mean I get real anxious about it.

My dad - who talks to Alik at least four times a day - tells me Alik got the email and is down to talk. The phone tag feels like I’m trying to lock in a big deal actor for my indie film, or an exclusive one-on-one with a major mafia dude who hasn’t been heard from in decades.

A week later I call Alik and ask if he’s game to talk, but he says he’s not feeling great and to call back another time. I say sure and we hang up. Is he avoiding it, or is he sick, or both?

I wonder if it’s all over, if this is as far as I can get, but a week later, a week during which, no joke, Onyx almost dies at least twice to remind me that I do need to keep going, I call Alik again. And he answers. And we talk.

Intergenerational Trauma Bonding

Before I can even ask a question, the words pour out of him, a torrent of feelings having finally found someone willing to listen.

He spends his days, he tells me, thinking about all the questions he would ask the people that aren’t around anymore. Like what, I ask him, and he can’t give an example - “all of them,” he says, as if the weight of them all makes trying to face any one of them impossible.

He tells me about living in Odesa, Ukraine with Emma and my dad and aunt in a communal apartment with three other families - “everyone shared one bathroom with one toilet. There was a place for each family to put their newspaper...”

I laugh, thinking about each family having their own reading materials while pooping when he finished his thought “...because there wasn’t anything else to wipe your butt with..”

“What are you laughing at?” he says.

“I mean it’s funny isn’t it?”

“It’s funny today, maybe.. What, you think we had toilet paper?”

I must say that these quotes, written in English onto the page, do not do Alik’s words justice. There’s a poetry to how he speaks, a depth reverberating through each word, the Russian language spoken through his raspy, weathered voice makes even the mundane feel profound.

I ask him how life was back in Ukraine. He answers with short, staccato phrases, like a poem:

It was good and

it was shitty,

but we lived.

there wasn’t any other way to live.

the way life was

was the way life was

so, we lived.

When he finishes I ask him what was good about his life back in Ukraine.

“What was good?,” he replies, “We were alive. We didn’t die during the war.”

I ask if there was a meet-cute for him and Emma, except I don’t say meet-cute because I have no idea how to translate that concept.

Love and work

Like my parents, Alik and Emma met at a new years eve party.

“I took her by the hand and said ‘that’s it, you’re gonna be mine’ and that was it.” It sounds more romantic and less weird than the translation through language + age + culture that you see here on the page, I think.

He tells me how he worked at ONE place for forty (40) years - a fabrics factory where he built and maintained mechanical parts often working on equipment that weighed more than five tons. Every weekday and most weekends, two shifts a day, for forty fucking years. He did that job for longer than I have been alive, and I’m sure never had the thought “man I would love to quit this job and pursue my passion of improv comedy.”

I ask “did you enjoy the work you did?”

“What else would I do?” he asked, incredulous. “Enjoying work? What does that even mean, ‘enjoy work.’”

It wasn’t all bad, though - “our fridges were full, the tables were full of food, we had big parties, sixty to seventy people, we traveled to the baltics, tours in Germany and Poland.”

And yet, in spite of and perhaps because of all this, there is a deep love that shines through Alik’s words. He speaks of Emma, of the past, of the questions he wishes to ask that will never be answered with a sense of hope, at least for today. Some days, most days, the hope is gone.

Who can blame him? I feel hopeless at least fifty percent of the time and I’ve got it made in the USA shade.

Car talk

Eventually I do steer (heh) our conversation to cars. Seventeen years after my dad was born, the family finally got their first car - a Zhigoli. Alik could fix everything that went wrong with it, clarifying so as to not to toot his own horn (nice), because the Zhigoli was a simple car. Not like the cars we drive today in America. “We lived in a different time, I could take the carburetor out no problem, what can I tell you.”

He kept that one car for fifteen years and then sold it before moving to America. One job, one car, one Emma.

I tell him that I’m bad with cars and start to explain how bad things have been with the Prius when he stops me - “wait, wait wait wait, how do you mean, ‘bad with cars?’”

Worried he’s about to yell at me, I clarify, “Like, if there’s a problem, I don’t know what to do.”

“You don’t need to know! Take it to the station. Why would you need to know that sort of stuff?”

I have no response, so he continues: “Unless you make money fixing cars, don’t try to fix cars. Take it to the shop and take care of your kid. You make money writing.”

Except in Russian the way he says it is “pishesh smishesh” where ‘pishesh” means writing and “smisesh” is like a ‘yada yada yada’ etc sort of way of saying whatever the fuck you do, I don’t fully get it, but I know that you do it. Like if someone were talking about the company that made the iPhone and said “apple shmapple” or describing soy milk as “milk schmilk”, that sort of thing5.

“Let’s stop for today,” Alik says.

“Again soon,” I respond, “I’ve got a lot more questions to ask.”

“Excellent,” he says, and we hang up.

We had just talked for an hour.

My dad tells me that for the rest of the week, Alik seems noticeably happier. And I do too. We had broken the curse, at least for a short while.

The end for now

Since that call a couple weeks ago, Onyx has died no less than three times - the car is nothing if not consistent.

One night he just started to struggle, heaving and hawing, a long beeeeeeeeep indicating that yes something was once again wrong. After turning him off and on I realized the AC was no longer working. Climate change, am I right folks?

I texted Lenia who said that maybe the radiator needed more water, maybe it could be many things - to bring it to the shop tomorrow and he’d take a look.

But I knew taking Onyx back to that shop again and again would destroy his confidence, his will to live, so I decided: fuck it, I’m gonna try to fix him myself.

The next morning I opened up the hood and found the radiator, took a photo and texted Lenia. “So you just put water in here? That’s it?”

“Yes, regular water, no problem”.

Is this what fixing cars is? Just giving them some h2o? Much ado about nada!

I brought the water to my parched friend (insert religious comparison here) and said ‘Here ya go, big fella - drink’.

Onyx drank as if he’d never had water before. “Gas is fine but this? This is yum” I am pretty sure he said.

I turned him on afterwards and the AC worked better than ever. He was healed, and so was our relationship - he trusted me again, and I trusted myself. A Dobrenko. A car guy.

I didn’t ask Alik or my dad for help. Because I didn’t need to, because I knew what to do. Also because Lenia told me what to do.

Regardless, I’d like to think that in that moment I would have made the Dobrenkos proud.

Whether or not I actually fixed the problem is, of course, yet to be seen. Days later Onyx died again as I was backing up out of the driveway. Just like, died. I turned him off, then back on and he was fine. I can only assume it was a trauma response, him being back in the same spot he died that first time.

So many questions, many without answers. Like when Lauren asks me “Alex , don’t you think it might be time to get a new car?” and I say “sorry, you’re breaking up” and make a sshhsfsdhf sound like we are on a cell phone call even though she’s right in front of me.

Maybe the answers aren’t really the point. Maybe what matters is simply asking. I think that’s all what Alik wanted - to be asked. And so ask I did.

Another miracle

I was in the kitchen a few days ago trying to kill a fly with the ZAP IT! bug zapper I’d just bought when I heard my phone ring - it was Alik.

Alik was calling me.

Surely this was a mistake. A butt dial. Or news of a tragedy. “Hi?” I answered, meaning something more like “everything okay?”

But it was. He called just to talk, and talk we did: about Wilder, about Alik’s recent cooking kick (chicken soups, mostly), and of course the weather, our health, and the health of our cars. I didn’t get into all the nitty gritty of Onyx because I didn’t feel like I had to - or could, in Russian - but I think it was implied.

The same conversation as before, but different, like a coldness thawed warm, full of the many questions we ask one another, each translated best into one, simple thing: “I love you.”

I already know it will be the talk of the town - a story for that evening’s dinner time convos throughout the neighborhood: “Hey you know that guy with the baby? The one who always looks lost and frustrated like he’s gotta go do a poop? His car died! Right in front of his house!”

it was sick though he wishes he’d splurged and gotten floor seats - the ppl down there were losing their minds. next time he’s gonna get floor seats doesn’t matter the cost.

In the Uber on the way to Lenia’s shop I wonder if there’s an entire mafia underbelly to the Dobrenko family. My dad would be a computer guy and maybe Lenia owed him for handling a problem with a rival Borscht outfit in the 80s.

I recall how when I was a kid, twelve or so, another “uncle” who is also not my actual uncle once told me there was a Russian mafia operating under the McDonalds on Route One in the suburbs of Boston. I thought he was kidding, but what if he wasn’t? What if he was testing me, then and there: do you want to be part of the mafia under McDonalds?

Also, why say that to a 12 year old? He was, it must be said, in the manure business.

Hi Alik,

When we talk on the phone I always want to ask you more questions about your life. Here are some I would love to know your answers to:

what do you think makes for a good life?

what do you miss about ukraine

what lessons from life do you want to make sure Wilder and future Dobrenko generations understand?

what are some of your favorite memories from Ukraine?

How was it when you first moved to America?

How did you meet Emma?

What are some funny memories of you and Emma?

What do you think people in my generation don’t understand about life?

You are always commenting on how different things are for me and Lauren than they were for you and Emma - do you think this is a bad thing?

I have many more but this is a good list to get us started. Maybe you can think about these for a few days and then I can call you to talk about them?

Sasha

Words, much like automobiles, depend wholly on the language they are built in. Much like cars. A stretch? Limo? Sure, shmure.

Also v exciting about your pilot!

DONBRENKO is an incredible name punch up, A+