I got a perfect score on my SAT and all I got was this lousy feeling of never being enough

S1E1 is free now, pls read it before the season ender coming soon!

Season One: I’m (Not?) The Best? is soon coming to a close! The season ending essay is coming SOON and has a lot to do with the stuff in this essay so I figured heck why not let’s republish this one FOR FREE so everyone can read it.

Enjoy! (if you’ve read it already just use google translate and read it in a language you’ve always wanted to learn).

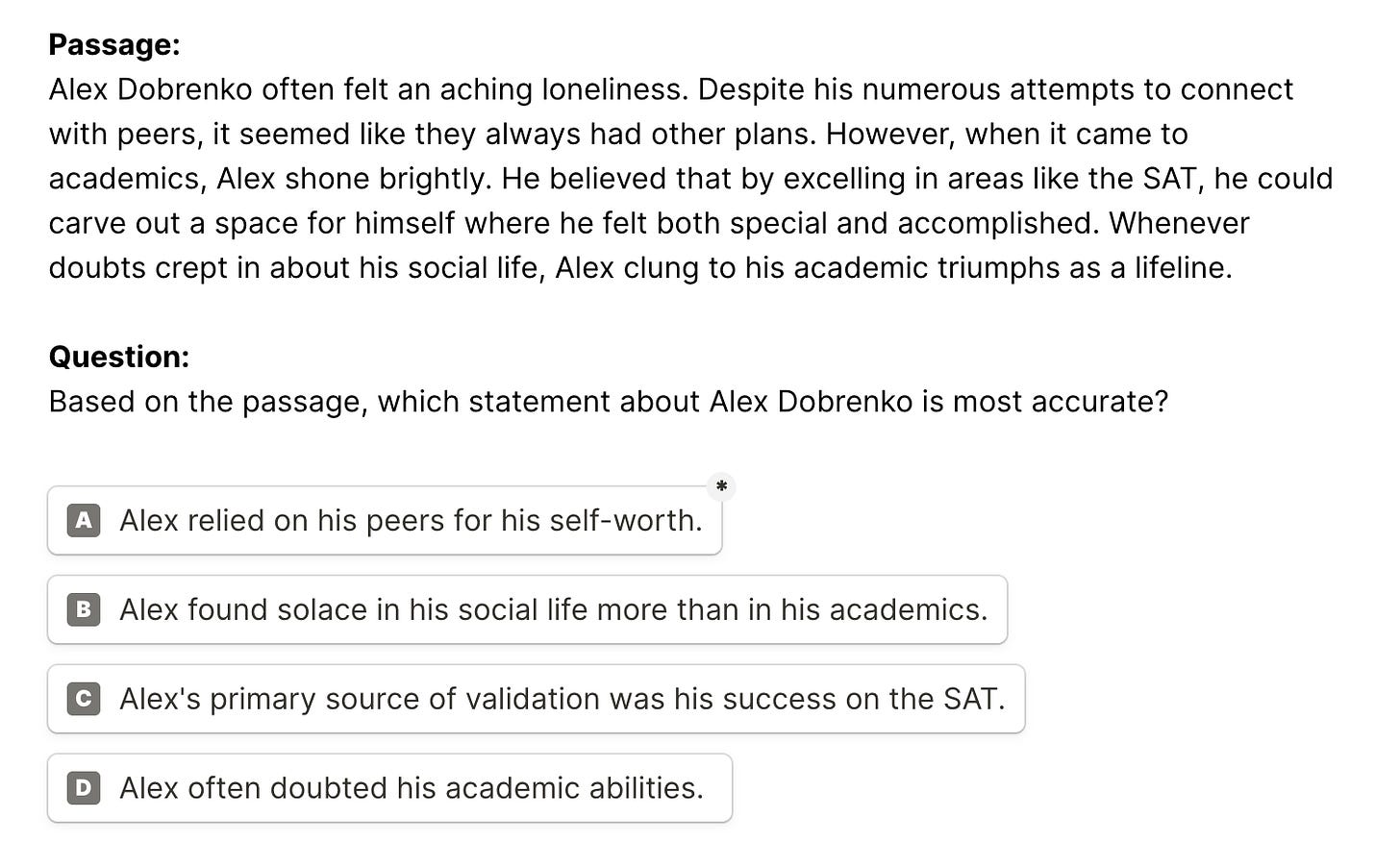

For most 4th graders in 1997, life was a cotton candy dream. They’d take care of their Tamagotchis, play 007 on N64, and rent Good Will Hunting from the local Blockbuster. Not me though.

I was busy.

I was prepping for the SAT1.

On Saturdays, most kids watched One Saturday Morning, Disney’s all-star lineup of cartoons including Doug, Recess, and Pepper Ann (much too cool for 7th grade). Not me though.

I was busy.

I was getting dropped off at Russian Math School where, from 9am to 1pm, I’d take practice SATs and get myself ready for the test that could change everything.

I was eleven years old, the SAT was six years away, and time was running out.

The ‘school,’ a remodeled basement of some Russian couple’s residential house, contained two ‘classrooms,’ each a bedroom sized space with three square folding tables and a giant whiteboard at the front.

Our class was five kids strong – me, the son of the Russian couple, two other Russian yo-yos and Tom Ling. Tom Ling and I were the two smartest kids there. Tom Ling was taller. He also had a cool jet-black bowl cut, but I was funnier. I was charming.

Our teacher, Eynstein, would stomp down the stairs at exactly 9am, his mop of frizzy hair shooting out in all directions as if he’d just emerged from an all night math bender so explosive that his pencil making contact with the paper caused an actual explosion.

That was his first name – Eynstein.

Einstein’s first name was Albert.

Our Eynstein didn’t look like a goofy grandpa with his tongue sticking out like he was rolling on the molly. He had more of a mad scientist super villain vibe – not manic, but focused, intense, and measured. He knew things, and soon we’d know them too.

His job, I remember him telling us, was an ‘actuary.’ To this day, I don’t really know what he did, but I knew he made a lot of money, which made everything he said important and true.

The SAT was an easy test, he explained, we just needed to know how it worked.

Each class would begin with a few practice sets. Fractions, powers of ten, the frikkin coordinate plane. Fifth grade stuff that we’d never do in school, but here we were and – get this – it all made sense to me. I was smart and I was ahead. There was a race of some sort, and I was winning.

I loved solving the problems. It put me in this flow state, and I was good at it. Each problem had a right answer – that was a given – and all I had to do was find it. It made sense. It was clean. And I loved being good at it. It filled me up with a pulsing am-ness – I was alive and I was seen and perhaps most importantly, people cared. Specifically, my parents cared. They were so proud.

Eynstein would read off the right answers in a heavy Russian accent. I’d get most right. Sometimes all. So would Tom Ling, that jackal.

Eventually, a smell of fried eggs wafted its way down from the kitchen – Eynstein’s wife Ana, who also taught us sometimes, cooked up some egg snack for us. And so we ate.

With nothing to compare it to, the whole thing, including the fact that 4th graders were preparing for the SAT, felt just about normal.

After eggs, we’d get 15 min to play basketball outside. I remember Tom Ling’s hair flopping around as he got super sweaty. Mine got sweaty too, but it looked cool. Here among the math school kids, I wasn’t just smart, I was cool too.

4th grade

We moved to America from Ukraine when I was seven years old in 1994. By 4th grade, I could pass for American.

A chubby-go-lucky little guy, I spoke English fluently and with no accent, thank you very much. Sure, my parents didn’t allow me to do the two most American things possible - eat McDonalds and have sleepovers – but still.

As a lonely only child, I craved friends. Now, I was ready. One Saturday afternoon after coming home from Russian Math School, I called up a few kids from school to see if they wanted to hang out. They weren’t friends but we were friendly. Mike wasn't home and Ben's mom said he couldn't. Oliver said he'd call me back later.

Samantha lived down the street. We weren't friends exactly but whatever. I pulled out our school's booklet, found our class list, and dialed.

HI, Samantha this is Alex. Do you want to play?

Oh hi, she said, um...I'm sorry i can't right now I'm busy. I'm watching my sister.

Oh no problem. Maybe I could come over to your house?

…No I don’t, no I don’t think my parents would want that.

Determined, I called every single kid on the class list. I wrote a little note next to any kid who said they might be free later.

This sort of thing happened a lot. I had Russian friends from the apartment building, but they didn’t count. I needed American friends. One time, a kid named Jason came over and we stood outside for thirty minutes playing with his cool airplane toy until he said he wanted to go home. I cried for a long while after that.

Young and gifted

Three armpit hairs later and I was in middle school.

At Math School, we were bigger and definitely sweating a lot more during the 15 minute basketball break, but everything else stayed just about the same. Algebra and geometry in 7th grade, Algebra II and Trig and Pre-Calc in 8th grade. Still ahead of schedule.

Our scores were improving, too. Eynstein and Ana recommended we all take the SAT. Not the PSAT, that was for pussies (that's what the P stood for, he told us ok no he didn't but can you imagine).

With a high enough score, we’d be accepted into the John Hopkins Center of Talented Youth. It wasn’t clear what that meant or what we’d get as a reward but boy howdy did I want it.

So I waddled my way into a high school testing center at age 12 and took the SAT surrounded by real bonafide high school juniors and seniors with their long legs and pretty faces. A few even had goatees. I felt important here. Special, the way you do when you hear about a kid who graduated from high school when he was 14. Wow, that kid is smart, you think to yourself. That was how I felt. Smart. Advanced.

Six weeks later, a fat envelope from The College Board arrived. My score.

I’d scored better than 92% of high school juniors and seniors. I don’t even remember the score, all that mattered was the 92%. I was smarter than almost everyone in high school. Incredible.

Another letter soon came from John Hopkins congratulating me on becoming part of the Talented Youth program. Compared to other 7th and 8th graders, my score was in the top 98% of kids my grade. They’d done a talent search and they’d found me. I even had the certificate to prove it.

Those numbers became my secret identity – I was the best and no one even knew it. But I did, and that helped me not feel like garbage. Especially the 92% – that was seared onto my soul. I wasn’t THE best, I was better. Those 8% must have been try-hard losers. The 4 hour a week Russian math school notwithstanding, I was pulling it off naturally. I was smarter than basically everyone. I was special. I was whole. I was a talent, and people - my parents, Eynstein, and John Hopkins – were impressed.

Good Will Hunting

Of the three movie heroes available to preteen boys in the late 90s – The Matrix’s Neo, Fight Club’s Tyler Durden, and Good Will Hunting’s Will Hunting, I was certainly the lattest. Lattest should be a word. That’s what Will Hunting would say. Played by Matt Damon, Will Hunting was a self-taught prodigal genius who effortlessly solved the world’s hardest math problems while working as a janitor at MIT.

Will Hunting became my old testament, quickly eclipsing years of whatever it was I learned at Hebrew School. His story was everything I wanted. Especially how other people noticed his talents and loved him because of it.

He was from Boston, I was sort of from a nice suburb near Boston. He was a genius. I was pretty good at math. We were basically the same guy. He was broken because his foster dad hit him. I was an only child to loving parents who'd given up everything so I could have a better life. We were exactly the same guy!

High School

One caterpillar-looking mustache and hundreds of conversations about girls' butts later and middle school was over.

Emotionally, I was a puddle of flop sweat. But mathematically, I was ready.

“I remember teachers really liking you, but also really not liking you,” my best friend Nate said when I asked what he remembered about me from high school, “because you were that annoying smart kid who was so smart you didn’t have to pay attention so you could goof off and make funnies.”

And funnies I made, especially in 9th grade math class. We were learning geometry and proofs, but I knew it all already. Eynstein had taught me. I funnied around until the teacher could not handle it anymore. She then ‘let’ me just sit at the back of the room and do whatever I wanted while she taught up at the front. Exempt and exceptional – I was rewarded. They had to. I was crushing it and ya know who wasn’t allowed to sit in the back? Tom fucking Ling.

Since I’d become a Talented Youth, our mailbox was stuffed full of pamphlets from universities trying to get me to apply. I felt like the high school athlete that everyone was scouting. “Have you seen this Dobrenko kid slash his way through the xy-plane? Kid’s doing math at an 11th grade level and he’s only - get this,” he’d say in a hushed tone, “ – a 9th grader.

The other scout, older and wiser, bald by choice, exhales his cigarette smoke and says, “Yea…that’s one of Eynstein’s boys. Kid’s going places. Fast.”

I still went to Russian Math School every Saturday. It wasn’t clear if I’d ever stop going, and I never asked. Some part of me loved being there, a place where I was noticed and special and challenged. My math and english scores kept creeping up to the magical perfect number of 800 but never quite hit it. A few 790s, a lot of 750s, some real stinkers in the 600s.

Jr yr

Several failed attempts at joining literally any of the running-based sports (track, cross-country, fuckin relay races), and it was junior year of high school.

That year was spent realizing how hard it was to get into good schools and doing everything I could to make myself a better candidate. All AP classes? Sure. Seven clubs that I had no interest in? Fine. Chess team that was usually just chess club because only the top five kids got to be on the team and I was right on the border? Fine.

Finally, Russian Math School was done. There was nothing more Eynstein could teach us. Just remember the rules, he told us. And keep practicing.

So I did, filling my time with practice tests that blurred together, one section to the next. The practice sections blurred together as I tried to decode the patterns of the multiple choice answers – D A B B C A without a single E ??? Yea right.

My dad drove me in our RAV4. I’d just started drinking coffee so I was jolted, but I wasn’t nervous. I was like a soviet gymnast who’d been training for the olympics since before he could walk.

The results came back and I’d somehow scored an 800 on the English? Strange, because I was not a writer nor would I ever be that was a dumb job for idiots.

I got a 790 in Math.

I was furious. Ten points away from a perfect score, and I couldn’t do it? It was right there. So close, but I blew it, fucking idiot. Classic Alex stuff to get close to perfect but not be able to get there. Pathetic, really .

Take two

One summer devoted to losing weight by running every day, counting my calories and only eating little yogurt cups, all of which resulted in a negligible amount of weight lost later and it was senior year. Time to retake the test.

This time, it was personal. This time, I drove the RAV4 myself. I was ready.

Back then I would often ask God for things. “If I change the channel to TBS and there’s no commercial, I can watch porn. Sound good, God?” I’d then turn the channel to TBS and, if there was a commercial, I’d try again with TNT.

For the SAT, I went above and beyond and promised God I wouldn’t watch porn for a week if he helped me do well on the test.

I stuck to my end of the bargain and so did God. Six weeks later, the 800 in math came back.

I’d done it. A perfect score. Everyone was thrilled – my parents, Eynstein, Ana. I didn’t feel much of anything though. What was the point of celebrating something that had already happened?

You studied for eight years, my parents told me, you should be proud.

Yeah, I’d say, thinking only about how a real smart kid wouldn’t need all that time to prep. I was an idiot barely skating by and if I didn’t get my shit together, I wouldn’t get into any college at all.

The SAT

In The Aptitude Myth, researcher Cornelius N. Grove argues that the SAT is just one of the many consequences of the Western idea that each child is born with a 'fixed set of givens.' The purpose of education, then, becomes helping each child achieve that which they’ve been naturally bestowed. The SAT - standardized aptitude test - closes the loop by testing each child on their math and reading / writing aptitude. Their natural ability. Except it doesn't. It's a test of one's affluence and access to prepare for the test.

In the 1920s, the SAT changed from 0-100 scale to 200-800 to make comparing the scores of students easier. Rather than look at five applicants who scored a 90, admissions offices could see five applicants whose scores ranged from 1400 to 1430.

I remember wondering why the scores were up to 800, but there was no time to figure it out. I had to keep prepping.

Now I'm realizing I never really stopped.

Now, as an adult in his mid thirties, I feel as though I’m always taking a test, the results of which will determine whether anything good happens in my life.

It’s everywhere.

We’ve got an hour and a half till soccer practice which my brain reads as TIME IS RUNNING OUT.

We’re potty training Wilder right now and he has an accident which I read as A GIANT FAILURE BECAUSE EVERYTHING MUST BE PERFECT.

Lauren shares a problem she’s having and immediately I go into MUST SOLVE THIS PROBLEM QUICKLY AND BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY.

Substack? A competition. Twitter, Facebook and Instagram too. Salary. My self-worth is my score and I AM NOT PERFECT FAR FROM IT I AM LOSING.

I AM A LOSER.

I am nothing until I am something.

When I wake up from naps I immediately check some website that can tell me in some way how I am doing because I don't know who I am without it. I am nothing like not a nothing nobody but a literal empty space upon which a score can be projected and internalized, a ranking subsumed and made whole. I am the number you tell me to be, and yet one thing is certain, always, no doubts, that it is not enough.

My parents wanted me to go to Harvard or nowhere else. Just Harvard. For immigrant parents, it was the only school that existed. College meant Harvard or…something else. Win or…lose.

I applied to Brown University instead. I got in.

I’d literally not watched porn for a month, so God was like ‘ok yea this man down bad.’

I’ll never forget my parents and I standing there, in my room, holding the acceptance letter. My mom was crying, my dad’s face beaming. They were the proudest they’d ever been.

And for a moment, I felt good.

But then the moment was gone and there was more work to be done. Soon we’d get an email about a cool new networking site called Facebook where we could meet our classmates. We could become friends and like each other’s posts. Just as the numerology of high school faded, the land of the quantified social self began. Very, and I cannot stress this enough, cool!

I had a lot of fun at Brown. I even learned something. Literally, one idea has stuck with me, and it came from a political science class called City Politics.

The lesson was simple – no matter the reason why an organization is initially created, its number one priority then becomes keeping the organization itself alive by any means necessary. Even if it means going against the very thing it was created for in the first place. That blew my mind. It still does.

Have I been created, molded, and trained to be a one-man organization hellbent on creating and protecting his sense of self on impossible-to-achieve success? The goal is to strive for more, for better, for the impossible, which means actually achieving any of those things doesn’t mean diddly doo.

I KNOW that the SAT doesn’t test aptitude, and still I crave the delicious swell of pride when someone finds out I went to Brown and they go, “ooooh, Brown???” like I’d just said I played bass guitar for The Sex Pistols. Even more so with the SAT score. I’d never bring it up because I am Humble and Good but when someone else does and people learn about my score, I love that. Because it becomes clear that I am special and that everyone knows it.

I understand that life is not the SAT, but I struggle to believe it.

Good Will Hunting isn’t really about Will being a genius – it’s about how what matters is everything else – the stuff Will refuses to let in because it might hurt. Because it might disappear. Like Skyler (Minnie Driver), his best friends, his therapist Sean (Robin Williams) and Skyler (Minnie Driver), the girl he falls in love with.

During one of their sessions (not the infamous ‘it’s not your fault’ one) Sean tells Will about how he left one of the biggest Red Sox games in history to talk to the woman who would become his wife. He had to go see about a girl.

The movie ends with Will doing the same, taking a chance on something that may destroy him while saying fuck you to all the things society tells him that he needs. He’s going to follow Skyler to California and leaves Sean a letter saying as much – he had to go see about a girl. I want that now like I wanted that then.

And yet even still, knowing everything I know about how the SAT doesn’t test aptitude but preparation, I still crave the adulation and awe that comes from being seen. Recognized. Special.

Of course, it’s not all bad. The SAT taught me to work hard and to strive for impossible things. It afforded me many opportunities in life including the very freedom to think deeply about questions like these.

It’s hard to accept, the idea that things aren’t your fault. Because it means the good things may not be yours either. And when you go all in on your identity being an endless stream of those good, extraordinary things, letting go feels terrifying.

But what choice do I have? It isn’t my fault, but it is my gift and my curse, one that I’ll be wrestling with for the rest of my life.

I’m not the smartest guy around, and I am worthy of love. I cringe writing that, but I know it has to be true believe my son Wilder is, and if he is then I must be too.

He is worthy of love for no other reason than being alive, a fact I anticipate spending the rest of my life making sure he understands. Maybe I’ll even glimpse the truth for myself. Maybe. Not enough information to determine an answer, not yet.

I know life isn’t the SAT, and I’m starting to maybe believe it too.

But it isn’t easy (post script)

What’s it called when you’re hangry all the time but you’re not actually hungry? That’s how I’ve felt lately.

This essay has been more of a doozy than most. It might in fact be the dooziest. This isn’t stuff I talk about often – doing so takes me back to a mindset I’ve tried hard to get away from – the comparing, competitive, need to be the best, to be perfect, exceptional, extraordinary.

Yesterday morning, I finished the 6th draft of it - 16 pages long and going nowhere fast. I hadn’t slept and we had a baby doc appt in an hour to check on #2. Lauren sensed something was off and said “if you want to not go to this appt that’s okay I won’t be mad.”

And I responded like a sad wombat “I’m so tired.”

To a 6 month pregnant woman. I said I was tired.

I asked if she was sure it was okay and she said yes and I went to the bedroom to nap. I needed it. But it felt wrong.

There I lay, an all too familiar shortness of breath overwhelm and rage seizing my body. Out of control, and underwater, this was how I always felt when faced with something big and impossible.

It was how I felt in all academic situations, testing and otherwise. Finishing a term paper, hanging in my thesis script, writing a proposal for work and now writing this very essay – my life had become a big series of these sprints towards perfection at the cost of just about everything else.

And here I was doing it again. Guilt flooded my brain as Lauren got ready in our bedroom. Should I just get up and go? But I was really tired and I needed rest I’d probably just go and then be a snippy lil asshole which no one wanted. I’d sleep.

I listened as she walked to the front door and opened it and realized I was doing it again, putting the pursuit of perfection above being there for my family.

“Lauren!” I screamed.

“Yea?” she answered.

I ran out of the bedroom in my undies and said, “I’m gonna come.”

She smiled and said okay.

We decided not to learn the gender of the baby beforehand, but for the sake of the line, let’s just say I went to go see about a girl. Or a boy. Who cares. I went to see.

Support my art

A nice big chunk of my income comes in (lol) from paid subscribers of this newsletter. If you’re loving the writing and in a position to do so, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Big or small every paid sub helps me so so much thank you.

Comments

Are you always in Be The Best mode? If not how?

What’s your relationship w standardized tests?

What stuff do you want me to explore this season?

How are you?

No, really?

What’d you think of that earnest ask to subscribe? I’m trying it out as I read Amanda Palmer’s book The Art of Asking which is about how to ask for help (who woulda thunk). Anyway lmk.

The Standardized Aptitude Test which, along with its counterpart the ACT, played an insanely outsized role in determining what college you got into

This post is making me laugh, because my husband was friends with your SAT tutor many years ago! He lived in Moscow in the mid-80s and was friends with Eynstein (whom he called Eynyick). He always wondered about the effects of placing so much pressure on a child by naming him after Einstein and wondered what would happen to him. I guess we know now!

I had a dream I was no longer a BAT subscriber wtf NIGHTMARE